This policy paper proposes priorities for the next Brazilian government to accelerate public policies for rebuilding and transforming the country in line with the 2030 Agenda and other international commitments, prepare it to tackle major global transformations, and recover its international protagonism. It also proposes an ecosystem and mechanisms to implement this agenda.

Brazil's diplomacy traditionally sees foreign policy as "State policy" with certain long-term objectives and standards of international action (Lafer 2011, Burges 2016, Saraiva 2020). With economic deregulation and democratization, Brazil's foreign policy was increasingly perceived as a public policy anchored in our diplomatic tradition and shaped by the multiple visions, practices, and interests of institutional and non-State actors (Lima 2000, Milani & Pinheiro 2013, Saraiva 2020). Public debate has since then focused on how those players interact to design and implement Brazil's foreign policy (Milani 2015).

Less attention is given to how public policy and foreign policy combine in a strategic and forward-looking agenda with dual focus on Brazil's sustainable development priorities (Cooper 2019, Faleiro 2022), on the one hand, and the transformations in international relations (Gaetani and Teixeira 2021) on the other hand. This strategic and forward-looking agenda should operate as a two-way street where foreign policy informs and enhances public policy while public policy guides foreign policy and contributes to buttressing Brazil's soft power internationally.

Based on that premise, a strategic and forward-looking agenda must: (i) seek international partnerships and funding to enhance public policies in line with Brazil's international commitments; (ii) anticipate, assimilate, and understand the disruptive potential of global transformations and act to minimize the risks and to maximize the opportunities those transformations bring to Brazil; and (iii) cause Brazil to re-engage and regain its standing in different regions and spaces for political and economic negotiation and cooperation.

This policy paper[1] suggests what issues and actions should be included in a strategic and forward-looking agenda with three main objectives. First, to accelerate public policies to rebuild and transform Brazil. Second, to prepare Brazil to tackle major global transformations. Third, to cause Brazil to re-engage with the world and regain its international standing. This policy paper further proposes mechanisms to institutionalize that strategic and forward-looking agenda and to build an ecosystem that can bring together different players, integrate positions and infuse an enlightened perspective that will help Brazil navigate with confidence and purpose in an increasingly complex world.

This is a timely discussion on a strategic and forward-looking agenda because a new federal administration will take over in January 2023. In the 2000s, Brazil achieved ahead of schedule several United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).[2] This success was possible thanks to society's engagement and public policies that fostered Brazil's development and enhanced its standing in the promotion of international development. Brazil must reposition itself and stimulate sustainable and inclusive development at home and abroad. The actions mentioned in this policy paper stem from our direct observations, studies, dialog, and interactions with experts in Brazil and abroad and are offered for discussion in the following sections.

ACCELERATE PUBLIC POLICIES TO REBUILD AND TRANSFORM BRAZIL

The starting point of a strategic and forward-looking agenda is enhancing public policies in line with Brazil's international commitments. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have operated as a "compass" (Gaetani & Teixeira 2021) for public policies around the world since UN member countries agreed to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015a). Approved in 2015 with leading Brazilian participation, the 2030 Agenda represents the culmination of a process initiated at the Rio+20 conference in 2012. It establishes 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 associated targets covering urgent economic development, environmental protection, and social inclusion issues.

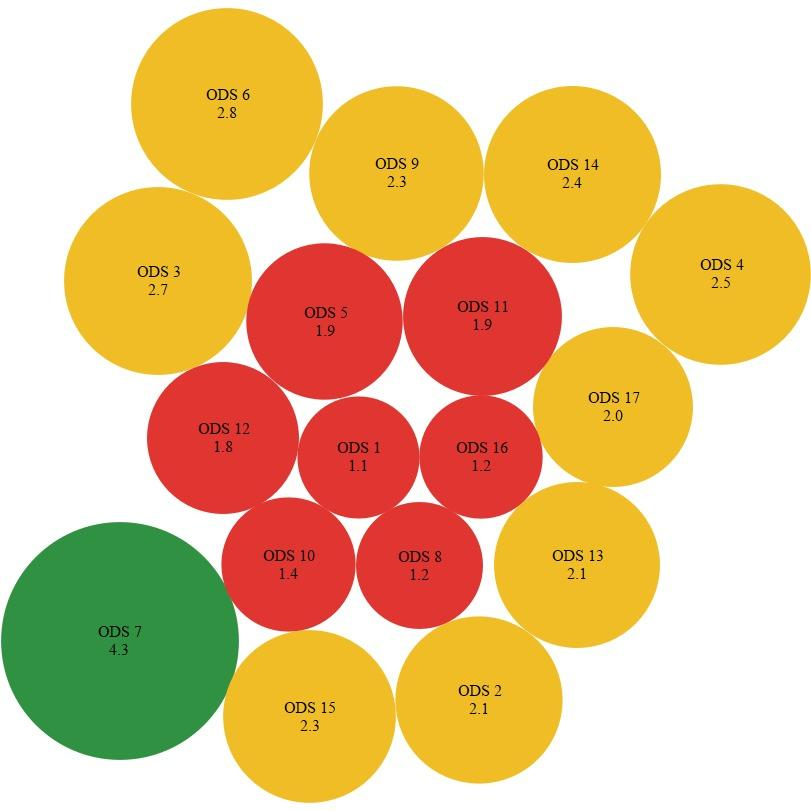

Once a shining example of success in MDG achievement, Brazil is now a laggard. According to research made for the Brazilian Development Association's (ABDE) 2030 Plan, Brazil has regressed in relation to or will not timely meet seven SDGs, is stagnant in relation to eight, and has advanced or already achieved only one. Brazil is performing worst in relation to SDG 1 (poverty eradication), followed by SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 10 (reducing inequalities), and SDG 16 (peace, justice, and effective institutions). The worst bottlenecks are in the North and Northeast regions, especially regarding income and unemployment (SDG8) and SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) in relation to transportation infrastructure and to the share of technology-intensive industrial sectors (ABDE 2022). Figure 1 shows Brazil's SDG completion progress.

Figure 1 - Brazil's SDG completion progress.* Source: Base study that supported ABDE's 2030 Plan (Vazquez et al. 2022).

* Each SDG target indicator received a zero to five score depending on the progress of its completion. A simple average was then calculated for each SDG. Green circles represent SDGs with average scores greater than 4 (advanced or achieved); yellow circles represent SDGs with average scores between 2 and 4 (stagnated); and red circles represent SDGs with average scores between 0 and 2 (regressed or will not be achieved).

Public policies the world over have been redesigned to achieve SDGs in an effort that is expected to gather speed during this "decade of action."[3] The social and environmental crisis, inflation, restrictions on development funding,[4] and geopolitical instability make such an effort more urgent in Brazil. By refocusing its public policies on the SDGs, Brazil will also align with other countries’ policies and join the development efforts of international lenders and other multilateral institutions. That rapprochement will favor the construction of partnerships and attracting foreign funding that can enhance sustainable and inclusive development.

Recreate national governance for SDGs

A strategic and forward-looking agenda to accelerate public policies to rebuild and transform Brazil should include 2030 Agenda governance, funding, and tracking tools. The new federal administration should, in its first six months, re-activate national-scale SGD governance by establishing a Policy to Promote the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,[5] by recreating the National SGD Commission (CNODS),[6] and by allocating clearly-defined roles to development financial institutions (ABDE 2022), to public policy designers and to government planning, budgeting, and management entities.

A strategic and forward-looking agenda to accelerate public policies to rebuild and transform Brazil should include 2030 Agenda governance, funding, and tracking tools.

National SDG governance was initiated when the CNODS was organized, in the year following the approval of the 2030 Agenda. That sixteen-strong commission included representatives from municipal, state, and federal governments and from civil society. It received permanent technical support from the Institute for Applied Economic Policy (IPEA) and from the Brazilian Geography and Statistics Institute (IBGE). Its mandate was to promote the 2030 Agenda dissemination, internalization, interiorization and tracking in Brazil. The Small Enterprise Assistance Service (SEBRAE) was the only participant of the National Development System (SNF)[7] that was also a CNODS member.

This governance was reviewed in 2019, when the CNODS[8] was terminated and the SDGs lost importance on the president's agenda.[9] Since then, the 2030 Agenda has been promoted in Brazil through the efforts of some Federal Government entities and of the governments of São Paulo, Paraná, Paraíba, Piauí, and other states. The Federal Accounting Court (TCU), the Federal Prosecution Office, and the Judiciary have also contributed to promote the 2030 Agenda through their decisions and by aligning their institutional structures and internal planning with that agenda, especially in relation to SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) and SDG 17 (partnerships and means of implementation). In 2021, the Joint House and Senate Caucus in Support of the SDGs proposed a bill creating the 2030 Agenda Promotion Policy (PL 1308/2021) and the recreation of the government SDG institutional framework. The bill does not address 2030 Agenda funding and pends voting in Brazil's House of Representatives.

Align the 2030 Agenda and SNF investments with the public policy cycle

Second, Brazil should align the 2030 Agenda and SNF investments with the planning, budgeting, and public policy management cycle by including strategies to fund sustainable development in the 2025-2027 Multi-Year Plan (PPA), in the Budget Guidelines Act (LDO) and in the Annual Budget Act (ABDE 2022) during 2023. The Addis Ababa Agenda for Action on Financing for Development (UN 2015b) proposes creating sustainable development strategies that are coherent, consistent with each country's peculiarities, and supported by Integrated National Financing Frameworks (INFF).

Indonesia was the first country to develop an INFF to implement its national development plan and SDG action plan and to track the achievement of its sustainable development commitments. Indonesia's Ministry of Planning SDG Financing Center (BAPPENAS) leads SDG implementation and is tasked with creating, coordinating, and harmonizing policies. The Center also liaises with ministries and other significant players to forge a holistic approach to fund sustainable development, to develop innovative financing products and to mobilize non-government investments. More than seventy countries have or are developing INFFs today (UN n.d.).

Leverage Brazil's participation in regional and multilateral development banks

With regard to funding the 2030 Agenda in Brazil, Brazil should leverage its participation in regional and multilateral development banks, in particular the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the New Development Bank (NDB), whose CEO Brazil appoints, and also in the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). This can be done by supporting NDB expansion to other Latin American countries; by designing transactions and (co)funding projects to strengthen production chains and regional value chains and to integrate the sustainable infrastructure (Vazquez 2020); and through investments to supplement SNF initiatives, in line with the SDGs and with the actions of their other members in furtherance of the 2030 Agenda. Examples of said actions include India's International Solar Alliance, the China-led Global Development Initiative and the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Environmentally Sound Technology Platform developed by the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) group, among others.

In 2022, CAF approved a US$7 billion capital increase aiming at doubling its portfolio by 2030. IPEA estimates the NDB to have US$25-30 billion available for loans in 2020-2025 and US$45-65 billion in the subsequent five years. AIIB may have as much as US$120 billion for loans (Baumann 2017).

Resume publication of the Voluntary National SDG Report

Third, Brazil should resume publication of the Voluntary National SDG Report (ABDE 2022) to track the completion of the 2030 Agenda, measure what still needs to be done, and reaffirm commitment to multilateralism ahead of the UN Summit of the Future[10] in September 2023. Systematic tracking of SDG targets and indicators began in 2016, and countries are required to submit their voluntary national reports at least once within the fifteen-year timespan of the 2030 Agenda. More than 120 countries have submitted their reports reaffirming their commitment to tackling major global challenges. Brazil submitted its first and only report in 2017.

Brazil tracks less than half the internalized 2030 Agenda targets and indicators.[11] Updated statistical databases broken down by region and category of vulnerable social groups are available for less than half of those targets and indicators. In 2017, the TCU ordered that 2030 Agenda indicators be broken down by municipality and gender.[12] The unavailability of common classifications, measurements, and tracking for SDG-oriented NFC funding makes it difficult for Brazil's development financial institutions to compare and exchange information.

Keeping track of progress in relation to the 2030 Agenda will help Brazil design and fund public policies focusing on priority areas and will be a significant show of accountability to Brazilian society. Each point in SDG progress raises the standard of living of Brazil's population, improves economic productivity and efficiency, and protects and stabilizes the environment, all of which Brazil can use to enhance its soft power globally.

Keeping track of progress in relation to the 2030 Agenda will help Brazil design and fund public policies focusing on priority areas and will be a significant show of accountability to Brazilian society. Each point in SDG progress raises the standard of living of Brazil's population, improves economic productivity and efficiency, and protects and stabilizes the environment, all of which Brazil can use to enhance its soft power globally.

PREPARING BRAZIL TO TACKLE MAJOR GLOBAL TRANSFORMATIONS

A strategic and forward-looking agenda must also be attentive to the disruptive potential of major global transformations and promote actions that minimize risks and maximize opportunities for Brazil's sustainable and inclusive development at three levels. The first one encompasses Asia's increased geopolitical importance at the expense of the West, China's and India's augmented economic weight and influence on the ideas and principles that guide international relations, and the potential of markets such as South Korea, Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam for Brazil.

Currently, five of the world's largest economies are in Asia. China, South Korea, India, Indonesia, and Japan represent 32% of the total G-20 trade flows, 39% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP), 63% of the population and 18% of the world’s geographical area. China has already overtaken the United States as the world's largest economy at PPP, and India is expected to take the second slot by 2050, according to PwC and International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates.

The Ministry of Economy has reported that Brazil-China trade ballooned from US$6.5 billion in 2003 to more than US$120 billion in 2022. By 2021, more than US$47 billion of Brazil's imports came from China and medium- and high-technology goods represented 21.7% of that amount. In that same year, China took 31.3% of Brazil's exports (US$87.9 billion). Commodities such as soybeans, iron ore and oil accounted for 77% of Brazil's sales to China. China's greenfield investments in Brazil are estimated to have created 34,500 local jobs between 2003 and 2020 and are increasingly focusing on digital and green technologies (CEBC 2021).

Trade between Brazil and India grew from US$1 billion to US$4 billion in that same period, despite the fluctuations of 2012-2019 (IPEA 2021). Like its trade with China, Brazil should seek to diversify its exports to India, now heavily concentrated on low-value-added products such as crude oil, vegetable fats and oils, sugars and molasses, and copper ores, to include more complex goods. Industrialized products such as organic and inorganic compounds, fuel oils, insecticides, medicine, and textile yarns represent almost all India's exports to Brazil. India's investments in Brazil amount to US$8 billion and create 25,000 to 30,000 jobs. Those investments are mainly in information technology, pharmaceuticals, and electronics.[13]

This asymmetry in bilateral trade suggests Brazil should create diversification strategies to simultaneously increase the share of high-complexity and high-value-added goods in its exports and boost its sustainable and inclusive reindustrialization. Brazil can use partnerships with China, India, and other countries to obtain technology, create jobs, reduce emissions, integrate with new global value chains, and implement the 2030 Agenda (Assis 2022, Falsetti & Ungaretti 2022). China and India also defend the democratization of international relations to promote multipolarity, respect for State sovereignty, non-interference in domestic affairs, horizontality, and non-imposition of conditions and to create mutual benefits within a South-South framework.

China and India are MERCOSUR's first and fourth largest trading partners, respectively, and Brazil should push for a closer relationship between MERCOSUR and both countries and with Asian economic blocs. In addition to the two Asian giants, a potential MERCOSUR free trade agreement with Indonesia, Vietnam, South Korea, and Singapore reportedly could add US$1 billion to Brazil's GDP, create fresh investments and trade opportunities, and raise workers' income (SECEX 2021a, 2021b). Megadiverse countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam, now seen by Brazilian agribusiness as the "next China," may represent new export markets for sustainable agricultural products.[14]

The second major global transformation to which Brazil must pay attention is the technological-digital revolution and the advent of a new and more competitive production paradigm. That paradigm stems from industrial nearshoring, reshoring[15] and powershoring[16] and from other structural changes in global value chains that will affect market access, the future of labor, and international competitiveness. This paradigm shift compels Brazil to refocus production systems on inclusive and sustainable development.

Structural change is no longer feasible without neutral, resilient, and digitized industries. At the same time, sustainable economic development will increasingly require innovation and inclusion. Brazil should urgently act to enhance its labor skills, infrastructure, and capabilities for Industry 4.0 and its leadership in digital agriculture in furtherance of its competitive, inclusive, and sustainable development.

The third major global transformation is the energy transition. The carbon-neutrality commitment of the world's major economies will affect trade and investment flows and pressure global energy supply chains to adapt. China was the world's leading importer of crude and refined oil in 2020 with US$166 billion (15.3%) in imports from Russia (15.6%), Saudi Arabia (14.9%), Iraq (10.2%), Angola (7.29%) Brazil (6.84%) and other countries. Crude oil is a significant export to China. Brazil should be aware of the potential economic, environmental, and social effects should Chinese demand for fossil fuels wane and be prepared to reposition itself if that happens (Vazquez 2021).

That movement should also consider the opportunities that will arise in low-carbon industries and Brazil's competitive advantages. McKinsey estimates (Ferreira & Ceotto 2021) that Brazil's demand for voluntary carbon credits could reach US$1.4 billion to US$2.3 billion by 2030. Brazil would then account for 15% of the total potential market for nature-based solutions. Today, Brazil generates less than 1% of that amount. Reforestation, agricultural, and energy waste reduction projects can leverage Brazil's carbon credit generation and boost revenues up to US$15 billion (Reset 2022). The proceeds from carbon credit sales can finance the reforestation of Brazil's degraded pasturelands and contribute to combating hunger and poverty.

Brazil must redesign its public policies and reposition its diplomacy to address the shift in political and economic power from the West to Asia and the global transition to a more digital and low-carbon economy in alignment with Brazil's demands, capabilities, desires, and specific interests.

Attract FDI that can spur technological development and add value to agricultural and industrial production chains

To adequately respond to major global transformations, Brazil will need a strategic and forward-looking agenda that combines foreign direct investment (FDI) with technological development and adds value to agricultural and industrial production chains through international partnerships to develop research, development and innovation hubs (RDI). Major Thai cell phone carrier AIS has signed a cooperation agreement with China's ZTE to create a research and development hub for 5G technology in Bangkok. The two companies plan to jointly offer tablets , smartphones, business solutions, and build digital infrastructure for 5G technology in Thailand.

Brazil should further integrate RDI and FDI through cooperation and investment agreements including the transfer and joint development of technology to accelerate Brazil's technological catch-up and to foster investment in industries that can spur income growth, greater economic complexity and SDG completion[17] (Vazquez et al. 2022, Perrone 2022).

Boost MERCOSUR trade with India and Southeast Asia

Brazil should expand the list of products and the mutual preferences included in current MERCOSUR negotiations with India, Indonesia and Vietnam and push the bloc toward closer ties with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Brazil should also work on a package of trade facilitation agreements involving various industries and reflecting some of the innovative efforts Brazil and India have been promoting at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Those agreements could include specific chapters on non-tariff measures, local currency payment systems and technical cooperation in agriculture to support the sustained expansion of trade flows with India and the 2030 Agenda.

Support international alliances for renewable energies

Another proposed action is enacting the bill authorizing Brazil to join the International Solar Alliance. India and France proposed that initiative to the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP-21) in December 2015 to address common challenges to spreading solar energy. The agreement entered into force in 2017 and encompasses 102 signatory countries and 81 members. The Framework Agreement on the Establishment of the International Solar Alliance (PDL 271/2021) was approved by Brazil's Senate in October 2022. Joining the International Solar Alliance may accelerate the spread of solar energy in Brazil,[18] attract fresh investment in renewable energy and encourage Brazil's participation in negotiations for other alliances such as the global biofuels alliance, to be proposed during the Indian presidency of the G20 in 2023.

Create funding facilities to boost Brazil's and Latin America's decarbonization

It is just as important to forge closer ties between Brazilian development financial institutions and their Chinese and third-country counterparts in support of initiatives such as the Kunming Fund for biodiversity and of new streamlined funding facilities to advance Brazil's decarbonization, in parallel to initiatives such as the Climate Fund and Renova Bio.[19]

Brazil should also work to expand its and Latin America's access to the China-Latin America Cooperation Fund, to the China-Latin America and Caribbean Investment Fund for Industrial Cooperation and to the China-Latin America Special Infrastructure Fund in furtherance of global energy transition and of completion of the 2030 Agenda. China's development investment funds are estimated to have received US$155 billion in fresh capital from 2007 to 2019. Taking into account funds earmarked for Brazil and Mexico, Latin America and the Caribbean have the highest potential portion of that capital, totaling US$42.2 billion (Moses et al. 2022).

Position Brazil as a global leader in carbon credit generation

Brazil should use its competitive advantages as a springboard to attract foreign technology for investment in carbon sequestration projects, perhaps involving other Amazonian countries, that can contribute to making Brazil a global leader in carbon credit generation. Brazil should also join other countries in developing green taxonomies, such as the Common Ground Taxonomy - Climate Change Mitigation joint initiative of the People's Bank of China (PBoC) and the European Commission. Initiatives that improve comparability and interoperability with carbon credit markets in China,[20] Europe, and the United States are key to making carbon credits generated in Brazil fungible and sustaining cross-border capital flows.

Brazil should simultaneously advance South-South cooperation with Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo announced in COP 27 and include other countries with large tropical forest areas. Such efforts will help the countries most affected by climate change obtain better funding conditions for actions to preserve biodiversity and generate carbon credits.

RE-ENGAGE BRAZIL WITH THE WORLD AND REGAIN INTERNATIONAL STANDING

Finally, a strategic and forward-looking agenda must aim at re-engaging Brazil with the world and regaining international standing in a pragmatic and non-exclusive way. That means building on the best partnerships for the defense of national interests and of multilateralism, on the one hand, and cooperation to address transnational challenges and the provision of global public goods, on the other hand. The creation of a politically stable, prosperous and united South American environment, which cannot be achieved without Brazil's re-engagement, will contribute to Brazil's development and will strengthen Brazil's and South America's standing vis-à-vis major world powers. In order to promote a win-win relationship, Brazil must re-engage with regional forums for political negotiation and buttress its economic and trade ties with its neighbors.

…a strategic and forward-looking agenda must aim at re-engaging Brazil with the world and regaining international standing in a pragmatic and non-exclusive way. That means building on the best partnerships for the defense of national interests and of multilateralism, on the one hand, and cooperation to address transnational challenges and the provision of global public goods, on the other hand.

Renewable and transition energy can be a stepping stone for improved economic and trade ties between Brazil and other South American countries. Because it requires sharing physical facilities, natural gas may be a catalyst for South American integration. It will also extend development to lagging sectors in the region (IPEA 2016). With the exception of the Brazil-Bolivia, Argentina-Bolivia, and Argentina-Chile gas pipelines, political decisions have hindered the strategic plans agreed to such as the construction of the Great Southern Gas Pipeline, connecting Venezuela with MERCOSUR gas pipelines via Brazil. An alignment between progressive and moderately conservative South American governments will facilitate regional integration.

Brazil can use sustainable infrastructure as a driver for its rapprochement with Africa. As a result of its decade-long economic decoupling in the South Atlantic, Brazil exported a mere US$7.5 billion to Africa in 2019, mostly in primary products. Brazil has also relinquished its strategic role in the Gulf of Guinea and its significant economic influence derived from major investment and infrastructure projects in Angola, Namibia, and Mozambique. Bilateral trade with East Africa shriveled from US$362 million in 2011 to just US$80 million in 2019 (Instituto Brasil-África 2021). This scenario got worse after the pandemic.

Brazilian and African value chains can be expanded, improved, and integrated within the framework of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), a market estimated at US$2.5 billion and encompassing more than 1.2 billion people in fifty-five countries. The agreement is expected to increase African consumption to US$6.7 billion by 2030, provide access to cheaper inputs and services and help modernize agribusiness and industry. This will boost demand for higher value-added products in which Brazil has a competitive edge, such as machinery and components for agribusiness. The experience of projects such as ProSavana suggest combining investments with mechanisms that can prevent, mitigate or offset social and environmental impacts and contribute to food security and poverty reduction in Africa.

Brazilian exporters can also indirectly use the ports, roads, and economic corridors built under the Belt and Road Initiative to move their products to Indian Ocean Rim countries[21], where Brazilian presence remains small. Road Belt Initiative infrastructure projects in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique, such as the Nairobi-Mombasa Railway may boost East Africa's annual exports by US$192 million (Instituto Brasil-África 2021). To benefit from those projects, Brazil should promote trade and investment facilitation agreements in line with the 2030 Agenda and strengthen political ties with African countries.

Dialog with the United States and Europe can be fruitful given their growing interest in issues dear to Brazil such as climate change, democracy and economic development. Issues such as the environment can be used as springboards to build a non-exclusive relationship with China and other emerging economies. On the verge of becoming the only economy in the G-20, in the BRICS group, and in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Brazil is poised to assume a strategic role in the construction of global dialog. Brazil can use the India, Brazil, South Africa Dialogue Forum (IBSA) as a driver to implement that strategy taking advantage of India's presidency of the G20 in 2023, of Brazil's presidency of the BRICS and G20 groups in 2024 and of South Africa's presidency of the G20 in 2025 (Malhotra 2022).

Stronger dialog with South America

To re-engage with the world and to regain its international standing, Brazil must strengthen its dialog with other Latin American countries by rejoining the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). Brazil should also act to bring CELAC closer to other regions such as India, Africa (via AfCFTA), the Persian Gulf Cooperation Council (CCGP), and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) through the creation of specific dialog mechanisms. Brazil's return to CELAC and UNASUR and CELAC's closer ties with other regions can help Brazil and Latin America better position themselves in relation to the dispute between the United States and China.

Integrate Latin America's major producers of lithium and natural gas

Another attractive strategy is to help Latin America's major lithium and natural gas producers position themselves in relation to growing demand from China, South Korea, the United States, Japan, and other countries. The global demand for lithium in electric vehicles has increased exponentially in recent years. Argentina (18 million tonnes in reserves) has started production, albeit at a small scale. Chile boasts the third largest reserves (10 million tonnes), accounting for 26% of global supply.

The starting point for integration could be the ratification of Bolivia's Protocol of Accession to MERCOSUR (PDC 745/2017), Bolivia joining the MERCOSUR Structural Convergence Fund (FOCEM), and the creation within the organization of social and environmental standards for lithium mining, production, and trade. Brazil should also consider resuming negotiations to join the South American Energy Treaty, which will help improve the efficiency of power generation and consumption regionwide.

Reinvigorate Brazil's economic and political partnership with Africa

Another strategy to pursue is to reinvigorate Brazil's economic and political partnership with Africa through ratifying the São Paulo Round Protocol on the relaunch of the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP) among developing countries. The São Paulo Round Protocol will enter into force once at least four of its eight signatories have ratified it. To date, the Protocol has been ratified by India (2010), Malaysia (2011), and Cuba (2013). Two of the four MERCOSUR members, Argentina and Uruguay, have ratified. Brazil and Paraguay must do the same for the MERCOSUR ratification to be completed.

It is equally important to agree on cooperation and funding for sustainable infrastructure and biofuel production projects and for developing strategic industries in both regions. Brazil should also support the creation of an alliance of biofuel-producing countries during the Indian presidency of the G20 in 2023 and launch the G20+Africa Forum for cooperation and sustainable development during the Brazilian presidency of the G20 in 2024.

Build dialog and add vim to the global debate on sustainable development

Finally, Brazil can turn the pandemic and the war in Ukraine into an opportunity to build a dialog between major powers, emerging economies, and developing countries to find joint solutions to global challenges such as a fair energy transition, the eradication of poverty and food insecurity, the implementation of equitable health systems, peace and security, and digital governance. Brazil can also act to refocus the international financial system toward initiatives that accelerate SDG completion, promote climate action in the countries most affected and least responsible for global warming, and advocate debt restructuring for lower-income countries.

...Brazil can turn the pandemic and the war in Ukraine into an opportunity to build a dialog between major powers, emerging economies, and developing countries to find joint solutions to global challenges such as a fair energy transition, the eradication of poverty and food insecurity, the implementation of equitable health systems, peace and security, and digital governance.

Reinvigorating IBSA as a space for political coordination between the Indian, South African, and Brazilian G20 presidencies and the South African and Brazilian BRICS presidencies may be the driver for this effort in the next three years. IBSA should update its original 2003 targets and agenda to align them to certain G20 and BRICS priorities and to offer a positive Global South agenda for international development. Brazil should immediately review its position on India and South Africa's proposal for the WTO to suspend patents for COVID vaccines. Such a move could spur similar BRICS initiatives through the Vaccine Research and Development Center created in 2022.

Brazil could suggest to China the creation of an Alliance for the Eradication of Hunger and Poverty in the upcoming China-CELAC Forum meeting, drawing on both countries' experience in combating hunger and extreme poverty, on the importance of Latin America's agricultural prowess to China's food security and on the significance of the issue in one of the world's most unequal regions. The recently activated Africa-China Alliance for Poverty Alleviation will operate as a platform to share experiences and mobilize resources in support of poverty reduction and agricultural development in Africa.

INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF A STRATEGIC AND FORWARD-LOOKING AGENDA

The proposals mentioned above should be jointly implemented by municipal, state and federal governments and by civil society. The first step will be to create an SDG Department associated with the Office of the President to support CNODS and its working groups, track Brazil's SDG completion, prepare evaluation reports – in line with international trends and discussions on the post-2030 agenda, and in assistance of working groups – and coordinate the publication of the Voluntary National SDG Report.

The SDG Department could also conduct a national dialog with UN agencies in Brazil and, within the federal government, with the Economic and Social Development Council (CNDES), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE), and the Ministry of Environment. IPEA and IBGE could provide technical advice on the production of evaluation reports and the Voluntary National SDG Report. The National School of Public Administration (ENAP) could arrange SDG training for government managers and leaders while the ministries of Finance and Planning and the Federal Court of Auditors align the 2030 Agenda and SNF investments with the planning, budgeting, and management cycle.

The Special Department for Strategic Affairs of the Office of the President, the ministries of Finance, Planning and Foreign Affairs, and IPEA could develop studies and organize work groups to anticipate, assimilate and understand the disruptive potential of major global transformations; inform public policies; to guide and prepare meetings of the G20 and BRICS groups and other major conferences that Brazil will host; and spark projects and actions of structural significance for Brazil's position in relation to major global transformations.

Said entities could also organize the creation of a "forward-looking ecosystem"[22] connecting scholars and diplomats with policymakers to find opportunities for collaboration, bring fresh perspectives, confirm or find new priority areas, and advance projects of common interest to Brazil and its international partners. That ecosystem could draw on the experience of the Ministry of Agriculture to include a network of special advisors on China coordinated by a core group nested within the Office of the Vice President.

A final recommendation is that the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC/MRE), BNDES, and the ministries of Finance and Planning should engage in a coordinated action to explicitly align international development cooperation with funding for strategic initiatives in sectors that are key for Brazil and its international partners.

[1] The author thanks Adauto Modesto Jr, Carlos Timo, Edgard Porto, Filipe Porto, Gustavo Rojas, Ivan Oliveira, Jean Taruhn, João Bosco Monte, Lavínia Barros de Castro, Mayra Juruá, and Rafael Paulino for their comments on the preliminary versions of the text. The author also thanks the team of researchers, the Brazilian Development Association (ABDE), and the 50 interviewees from the ABDE 2030 Sustainable Development Plan for the reflections that contributed to this policy paper.

[2] Adopted in 2000, the Millennium Development Goals included goals to make the world better and fairer by 2015: http://www.fiocruz.br/omsambiental/media/ODMBrasil.pdf.

[3] In September 2019, global leaders gathered in New York created the Decade of Action initiative, a movement that began in the following January of the following year to accelerate the global SDG achievement.

[4] The change in strategy of government-owned banks has caused the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) loans to other development financial institutions to shrink from R$39.3 billion in 2014 to R$6.5 billion in September 2021. The 2017 review in BNDES interest rates further contributed to diminish the funding available to Brazilian development financial institutions.

[5] Bill (PL) 1308/2021.

[6] Decree no. 8892 dated October 27, 2016.

[7] The commission is composed of thirty-two federal- and state-owned commercial and development banks, development agencies, cooperative banks, the Federal Research Support Agency (FINEP) and the Small Enterprise Assistance Service (SEBRAE). Its mission is to fund strategic industries in furtherance of Brazil's development.

[8] Decree no. 9759/2019 dated April 11, 2019.

[9] Decree no. 9980 dated August 20, 2019.

[10] Proposed by the UN Secretary-General in "Our Common Agenda," the Summit of the Future will aim to reaffirm the UN Charter, reinvigorate multilateralism, boost the implementation of existing commitments, agree on effective solutions to challenges and restore trust among member states.

[11] According to SDG data on the IBGE and IPEA websites.

[12] Decision 298/2017 (TCU 2017).

[13] Information provided by India's Ambassador to Brazil, Suresh Reddy, in November 2022.

[14] Interview with Brazil's representative in September 2022.

[15] The terms nearshoring and reshoring mean bringing production chains closer to or into the country of origin, respectively. Both have been gaining ever more weight in U.S. and European agendas in connection with the trade war with China.

[16] According to Arbache (2022), powershoring refers to the decentralization of production to countries close to consumption centers and that offer clean, safe, cheap and abundant power and other features to attract industrial investments.

[17] The base study for ABDE's 2030 Plan for Sustainable Development (Vazquez et al. 2022) identified the industries with the greatest potential for economic (gain in complexity) and social (gain in SDGs) transformation in each macro-region.

[18] Solar power is estimated to grow by 7%-10% p.a. in Brazil after the change in the incentive policy. Interviews with representatives of a Brazilian development bank between August and September 2022.

[19] The usual requirements of traditional development financial institutions on the one hand encourage the internalization of the 2030 Agenda by Brazil's development financial institutions but, on the other hand, hamper access to funding by smaller institutions. The latter operate locally and have limited SGD-related capabilities and knowledge. Interviews with representatives of SNF institutions between January and October 2022.

[20] China considers using Internationally Transferred Mitigation Options (ITMOs) under Paris Agreement Article 6 generated in Belt and Road Initiative countries for offset purposes within its national Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) given the shortfall of Chinese Certified Emission Reduction (CCER). That may create a significant demand for ITMOs.

[21] South Africa, Australia, Bangladesh, Comoros, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Oman, Seychelles, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Thailand.

[22] Chile's Nueva Política Exterior (NPE) group is a progressive and non-partisan network that proposes to create knowledge, promote political dialog and contribute to Chile's foreign policy and international relations. The group uses dialog, research and outreach activities to promote cooperation between experts, decision-makers and other players associated with Chile's international relations.

References

ABDE. 2022. Plano ABDE 2030 de Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Brasília: Associação Brasileira de Desenvolvimento, 2022. https://abde.org.br/plano-abde-2030-apresenta-acoes-estrategicas-para-que-o-brasil-possa-atingir-os-ods/.

Arbache, J. 2022. “Powershoring.” CAF, November 14, 2022. https://www.caf.com/en/knowledge/views/2022/11/powershoring/.

Assis, M. 2022. “Lula e Bolsonaro alimentam expectativas sobre China e acordo UE-Mercosul.” Jornal Valor Econômico, April 4, 2022. https://valor.globo.com/mundo/noticia/2022/09/04/lula-e-bolsonaro-alimentam-expectativas-sobre-china-e-acordo-ue-mercosul.ghtml.

Baumann, Renato. 2017. “Os novos bancos de desenvolvimento: independência conflitiva ou parcerias estratégicas?” Revista de Economia Política 37 (2): 287-303. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-31572017v37n02a02.

Burges, Sean. W. 2016. Brazil in the world: the international relations of a South American giant. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

CEBC. 2021. Sustentabilidade e tecnologia como bases para a cooperação Brasil-China. Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Empresarial Brasil-China. https://www.cebc.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Sustentabilidade-e-Tecnologia_PT_21out.pdf.

Cooper, A. 2019. “Populism and the Domestic Challenge to Diplomacy.” In New Realities in Foreign Affairs - Diplomacy in the 21st Century, edited by Volker Stanzel, 33-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.5771/9783845299501-33.

Faleiro, A. 2022. “Política externa não existe no vácuo.” República.org, April 20, 2022. https://republica.org/emnotas/conteudo/politica-externa-nao-existe-no-vacuo/.

Falsetti, F. & Ungaretti, R. 2022. “A desindustrialização brasileira e o papel da China.” Observa China, October 24, 2022. https://www.observachina.org/articles/a-desindustrializacao-brasileira-e-o-papel-da-china.

Ferreira, Nelson & Henrique Ceotto. 2021. “Posicionando o Brasil como líder global no mercado de créditos de carbono por meio de reflorestamento e proteção de florestas.” McKinsey & Company, November 8, 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com.br/our-insights/posicionando-o-brasil-como-lider-global-no-mercado-de-creditos-de-carbono-por-meio-de-reflorestamento-e-protecao-de-florestas.

Gaetani, Francisco & Izabella Teixeira. 2021. The times they are a-changing: perspectives of the Brazilian sustainable development agenda. Policy Paper 4/5, CEBRI/KAS. https://www.cebri.org/media/documentos/arquivos/Papers_KAS2020_4_5_EN_times.pdf.

Instituto Brasil-África. 2021. Commercial Diplomacy: The Brazilian Path to the African Market. Instituto Brasil-África. https://ibraf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Policy-Brief-EG.pdf.

IPEA. 2016. América do Sul revela potencial de complementaridade produtiva. Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2952&Itemid=2.

IPEA. 2021 Brazil and India: Peculiar Relations with Big Potential. Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/10901/2/DP_Brazil%20and%20India_Publicacao_Preliminar.pdf.

Lafer, Celso. 2001. A identidade internacional do Brasil e a política externa brasileira: passado, presente e futuro. São Paulo: Perspectivas.

Lima, Maria Regina Soares de. 2000. “Instituições democráticas e política exterior.” Contexto Internacional 22 (2): 265-303.

Malhotra, K. 2022. “IBSA, G20 and the Global South.” Gateway House, October 20, 2022. https://www.gatewayhouse.in/ibsa-g20-global-south/?utm_content=226845356&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&hss_channel=tw-905477617775771654.

Milani, C. R. S. 2015. “Política externa é política pública?” Insight Inteligência XVIII (69): 57-74. https://inteligencia.insightnet.com.br/politica-externa-e-politica-publica/.

Milani, C. R. S. & Leticia Pinheiro. 2013. “Política externa brasileira: os desafios de sua caracterização como política pública.” Contexto Internacional 35 (1): 11-41. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-85292013000100001.

Moses, O. et al. 2022. China’s Paid-In Capital Identifying and Analyzing China’s Overseas Development Investment Funds. GCI Working Paper 025, 11/2022. Boston University Center for Global Development Policy. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2022/11/GCI_WP_025_ODIF_FIN.pdf.

UN. 2015a. Transformando nosso mundo: A Agenda 2030 da Terceira Conferência Internacional para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. New York: United Nations. https://brasil.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/agenda2030-pt-br.pdf.

UN. 2015b. Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (Addis Ababa Action Agenda). New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAAA_Outcome.pdf.

UN. no date. “Integrated National Financing Frameworks.” Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Financing. https://www.un.org/development/desa/financing/what-we-do/other/integrated-national-financing-frameworks#:~:text=Integrated%20national%20financing%20frameworks%20.

Perrone, Nicolás M. 2022. Technology Transfer and Climate Change: A developing country perspective. Climate Policy Brief 28 (November 14, 2022). https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CPB28_Technology-Transfer-and-Climate-Change_EN.pdf.

SECEX. 2021a. Estudo de impacto Acordo de Livre Comércio Mercosul-Indonésia. Brasília: Secretaria de Comércio Exterior. https://www.gov.br/produtividade-e-comercio-exterior/pt-br/assuntos/comercio-exterior/publicacoes-secex/serie-acordos-comerciais/arquivos/indonesia-estudo-de-impacto.pdf.

SECEX. 2021b. Estudo de impacto Acordo de Livre Comércio Mercosul-Vietnã. Brasília: Secretaria de Comércio Exterior. https://www.gov.br/produtividade-e-comercio-exterior/pt-br/assuntos/comercio-exterior/publicacoes-secex/serie-acordos-comerciais/arquivos/vietna-estudo-de-impacto.pdf.

Vazquez, K. C. 2020. “Impacto no desenvolvimento, parceria público-privada e integração regional: caminhos possíveis para o Novo Banco de Desenvolvimento do BRICS.” Revista Tempo do Mundo 22: 175-187. https://doi.org/10.38116/rtm22art8.

Vazquez, K. C. 2021. “Up or Out: How China’s Decarbonization Will Redefine Trade, Investments, and External Relations.” In Drivers of Global Change: Responding to East Asian Economic and Institutional Innovation, edited by Giuseppe Gabusi. Asia Prospects Report, Turin University World Affairs Institute. https://www.twai.it/articles/china-decarbonization-trade-investments-external-relations/.

Vazquez, K. C. et al. 2022. “Cinco missões para o desenvolvimento transformador do Brasil: metodologia e resultados do estudo-base do Plano ABDE 2030 de Desenvolvimento Sustentável.” Tempo do Mundo. In print.

Viri, N. 2022. “Mercado de carbono pode financiar reflorestamento amplo no Brasil, diz McKinsey.” Reset, November 4, 2022. https://www.capitalreset.com/mercado-de-carbono-pode-financiar-reflorestamento-amplo-no-brasil-diz-mckinsey/.

Submitted: November 4, 2022

Accepted for publication: November 16, 2022

Copyright © 2023 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.