The rupture caused by U.S. tariff policy jeopardizes the multilateral trade order. The U.S. retraction projects scenarios of multipolarity and opens space for greater prominence by China and the middle powers. Thus, a new configuration of the international economic order begins, marked by instability and hegemonic dispute. The intertwining of trade and finance issues becomes clear. Global governance faces uncertainties, opening space for new regional dynamics and a possible reconfiguration of the rules regulating international trade.

Note: the article was updated by the authors on July 18 to include recent facts on the comercial conflict.

Signs of exhaustion in the multilateral order built in the post-war period under US leadership have been apparent for some time. Mutual accusations and growing dissatisfaction pointed to a worsening of political and economic crises, but not yet to a possible rupture of the multilateral system. The arrival of the second Trump administration in 2025 represented an implosion of broad magnitude. Initiated as a tariff attack against China and the rest of the world – clearly within the framework of geoeconomics, using trade as a tool for political advantage – its effects are now spreading to the financial sector. They could affect the foundations of the global macroeconomy, exacerbating inflation and potentially triggering a global recession.

There is no room for doubt: the Trump administration is breaking with the foundations of the international order to impose a new geopolitics. By creating tensions with European allies, the US has reassessed NATO commitments, raising the possibility of a partition of Ukraine. The steps taken with the bombing of Iran point to a new configuration in the Middle East. This new dynamic raises, in turn, essential questions: will the conflict between the great powers, the US and China, be restricted to trade, or will it involve the division of the globe into spheres of influence and the absorption of Taiwan by China? In the Atlantic, will the US exert its power over Panama and Greenland? On whose side will Russia, currently China's ally, position itself? How will the European Union (EU), India, and middle-income countries react? What is the role of global governance organizations? Are we moving toward a world divided into three zones of influence (US, China, and Russia), or toward a bipolar world, with a radical separation (decoupling) between the US and China? Is the world heading toward armed confrontation?

The US is the world's largest economy, with a GDP of approximately US$29 trillion and 22% of total world trade flows (exports + imports). China, on the other hand, has an estimated GDP of US$19 trillion and represents approximately 25% of global trade flows. A trade war between these two economic powers will impact all other international partners and global governance.

The objective of this text is to analyze the current situation using geoeconomics as a framework. It summarizes the main points of the trade conflict, assesses the financial and economic implications, and builds a bridge between geoeconomics and the geopolitics of the new Trump era. Finally, it develops some scenarios with possible developments for the near future. The central question is who will conduct the global governance and how. how and by whom global governance will be conducted.

GEOECONOMICS ACCORDING TO TRUMP

The Trump era will most likely become a classic geoeconomic case of how to use trade weaponization to achieve geopolitical ends. According to Blackwill and Harris (2016), in their seminal work "War by Other Means," trade instruments have been used in recent decades for persuasion or coercion for political ends. International trade instruments such as tariffs, export or import restrictions, subsidies, regulatory barriers, as well as restrictions on the origin of investments or financial sanctions, are being increasingly used by countries with greater economic clout for political purposes. The use of such instruments has already demonstrated its effectiveness, but their consequences can be unpredictable. Trade conflicts can escalate into economic crises and potentially lead to military conflicts. History offers many examples of this progression.

It is important to summarize the main points of the Trump administration's trade strategy, already clearly outlined in the Presidential Memorandum "America First Trade Policy" released on January 20 (United States 2025a). This document serves as a guiding principle for the Trump administration's measures and casts doubt on the thesis that his administration acts purely and simply at the whim of the president's urgeswhims and instincts – even if the implementation of these measures is chaotic.

Trump's new trade policy uses tariffs as its primary weapon. The objectives pursued are: (i) reducing persistent trade deficits, considered a risk to US national security and generated (according to the Trumpian view) by unfair practices by international partners; (ii) repatriating industrial activities to the US; (iii) creating jobs for the US working class; (iv) modernizing industrial production; (v) generating revenues that allow for tax reductions; and (vi) bringing US trading partners to the negotiating table. The main points are outlined here.

The New US Trade Policy

The current administration treats trade policy as a critical component of American national security. The policy is designed to promote investment and productivity, strengthen industrial and technological advantages, and benefit workers. Its priorities are numerous: investigating the causes of unfair and unbalanced trade and persistent and growing deficits (US$1.2 trillion in 2024); establishing an External Revenue Service to collect trade-related tariffs and duties; reviewing the USMCA Agreement with Mexico and Canada; reviewing exchange rate practices between partners and the US; reviewing trade agreements; negotiating bilateral and sectoral agreements for access to new markets; reviewing anti-dumping and countervailing duty regulations; taking measures against counterfeit and smuggled products and reviewing the minimum rate for duty-free imports; investigating discriminatory tariffs against American companies; and analyzing government procurement agreements. It also intends to thoroughly review trade relations with China, including investment and intellectual property. Review the security of the industrial base, including steel and aluminum import practices, and review export control measures related to strategic goods, software, services, and technology.

China is the main target of the trade war.

The unfolding of recent events and the action and reaction measures between the US and its partners unequivocally demonstrate that the main target is China. Since it acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China has become the most significant power in global international trade, displacing the US in its trade leadership role.

Regarding China, the Memorandum establishes a review of bilateral relations to determine whether Chinese actions are in line with negotiated agreements and, if necessary, recommend appropriate actions such as tariffs; evaluate the report under Section 301 on intellectual property; apply tariffs, if necessary, regarding supply chains and circumvention by third countries; investigate measures deemed unreasonable or discriminatory against US trade (Section 2411 US Code); reevaluate legislation on agreements based on Permanent Normal Trade Relations with the People's Republic of China and make recommendations; assess the status of intellectual property granted to Chinese nationals regarding patents, copyrights, and trademarks; and make recommendations to ensure reciprocal treatment.

Tariff Rules

The foundations for tariff rules were established in the April 2 memorandum "Reciprocal Trade and Tariffs" (United States 2025b). This text assesses that the US has one of the most open economies in the world, with the lowest weighted average tariffs and the lowest trade barriers. It considers that the United States has been mistreated by both friendly and enemy countries and that the lack of reciprocity is one of the causes of significant and persistent deficits in merchandise trade, resulting in closed markets that reduce US exports.

The Fair and Reciprocal Plan of April 2 (United States 2025c) includes the following barriers to trade: tariffs; discriminatory consumption taxes (value-added taxes); subsidies; regulatory requirements; non-tariff measures; policies and practices that cause exchange rate deviations; and limits on market access.

To address the deficit problem, a "Reciprocal Tariff" was introduced, calculated according to a formula established by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). This formula was presented as a necessary tool to rebalance bilateral trade deficits between the US and each partner, combining tariffs and non-tariff factors. According to the text, since calculating the effects of tariffs and regulations on individual deficits for tens of thousands of products is complex, if not impossible, their combined effect was obtained by a proxy that calculated the compatible tariff level that would bring the deficit to zero. Furthermore, it justifies that, if the deficit is persistent due to tariffs and non-tariff policies, then the tariff rate compatible with nullifying these effects would be reciprocal and fair. The tariff applied to each country can be obtained by dividing that country's trade deficit by the total imports from that country to the US. Two selected price elasticities correct the value of this indicator in the proposed formula. The elasticities were set at two (2), dividing the tariff value in half, "by courtesy of the president," according to the government spokesperson. The formula presented by the USTR was the subject of intense criticism due to its simplistic nature and dubious economic basis.

Legal Basis

To rebuild the economy and restore economic security, the US president invoked his authority through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), as well as US Code Section 50 (1701); the National Emergency Act (50 E.S.C. 1601); and the Trade Act of 1974, Section 604. This legal basis is already being challenged domestically in the US.

The alleged reason is a national emergency, resulting from the large and persistent deficit caused by the aforementioned lack of reciprocity in trade relations and other harmful policies, such as currency manipulation and value-added taxes (VATs), used by many partners.

A 10% base tariff was imposed on all countries, in addition to individual reciprocal tariffs for countries with the most significant deficits with the US. The tariffs would be applied for a period to be determined by the president. In cases of retaliation or countermeasures, the tariffs could be increased. They could also be decreased if partners align with the US. Products not subjected to tariffs are: goods already subjected to sanctions (USC 1702(b), such as those from Russia); steel and aluminum; cars already subjected to tariffs (Section 232); copper; pharmaceuticals; semiconductors (with a broad definition of products); wood products; gold; energy and minerals not available in the US. In the case of the USMCA, goods included in the agreement will be excluded, and the remaining goods will be subjected to 25% tariffs; energy and potash will be subjected to 10% tariffs.

The document justifies the measures by pointing out that the average simple tariff in the US is 3.3%, in contrast to Brazil's 11.2%, China's 7.5%, the European Union's 5%, India's 17%, and Vietnam's 9.4%. It further explains that the trade deficit in 2024 was US$1.2 trillion and that the value of manufacturing in 2023 was 17.4%, a decrease from 28.4% in 2001.

Note that the application of these tariffs is highly complex, due to differences between the various partners and the rules of origin. The announcements of the application of tariffs, with great fanfare – followed by the publication of exceptions and confirmations – have generated immense uncertainty among economic agents. Tariffs are announced, excepted, and reconfirmed (or not) daily, at the frenetic pace of a "reality show," as Professor A. A. rightly pointed out professor Celso Lafer (interview with Band News on April 10, 2025).

It is worth emphasizing, again, that since the beginning of the Trump administration, several documents have outlined the main points and objectives of the new policy – even though its theoretical basis remains highly questionable. Therefore, the political direction was already known. Criticisms can indeed be leveled at the way this policy is being implemented. It is also possible to question whether the effects of its implementation were correctly anticipated and weighed.

TRUMP'S GEOECONOMICS IN ACTION – A CHRONOLOGY OF FACTS

To analyze the scale and impact of the US tariff package, it is important to examine the advances and setbacks in the use of a classic trade instrument – the tariff. The subject of several rounds of negotiations under the former General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the reduction of import tariffs and their consolidation in the WTO was achieved over time by a growing number of countries, reaching the current situation in the Uruguay Round and in accession processes since 1995. In the case of China, the tariff reduction occurred through negotiations in its WTO accession process, completed in 2001. With the negotiation of numerous preferential agreements, tariffs became a less relevant instrument in trade, given regulatory barriers (non-tariff barriers). It is important to emphasize that tariffs, as a trade instrument, have always been justified in the WTO to protect and promote domestic production, especially in developing countries. It should be noted that, according to a recent WTO study, approximately 80% of international trade still occurs (before President Trump's "tariff hike") based on multilaterally agreed tariffs, applied equally, without discrimination, to all trading partners, by the so-called "Most Favored Nation Clause" (MFN) (Gonciarz & Verbeet 2025).

The Trump package brought the issue of tariffs to the forefront of the current scenario. The president had already revealed his 's preference for the use of tariffs had already been revealed during his first administration. Based on Section 232 on national security, 25% tariffs were imposed on steel and aluminum articles, automobiles, and auto parts.

Below is a brief chronology of tariff changes during Trump's current term.

From January to early April:

That was the day Trump's trade offensive was announced, launched with great fanfare in the White House gardens, with tables, lists of countries, and figures. Some goods were excluded from the scope of the reciprocal tariffs. Excluded are: goods already under sanctions for national security reasons; goods within the scope of Section 232; copper; pharmaceuticals; semiconductors; wood products; gold bullion; energy; and specific minerals, a total of 1,039 8-digit HS products (Harmonized System, an international nomenclature for the classification of import and export products, with a standardized numerical method) valued at 20% of US imports.

For Canada and Mexico, under the USMCA, goods qualified as originating maintain their preferential treatment and are exempt. For non-qualified goods, the tariff will be an additional 25%. Energy and potassium, not classified under the agreement, will be subject to an additional 10%. To assess the size of tariffs for the most relevant trading partners, application ranges can be established:

- 10% – minimum base tariff for all countries;

- 10% – Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Singapore, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia;

- 11% to 19% – Israel, Norway, and the Philippines;

- 20% to 29% – the European Union, India, Japan, Kenya, Malaysia, South Korea, and Pakistan;

- 30% to 39% – China, Indonesia, South Africa, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, and Thailand;

- 40% to 49% – Vietnam.

In April:

In July 2025, at the end of the period granted for the agreements (July 9), the US announced a new round of tariffs, to be applied starting August 1, 2025, despite being in the process of negotiating with more than 50 countries:

- 50% – Brazil

- 32% to 40% – Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Serbia, Indonesia

- 30% – South Africa, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Algeria, Libya, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 30% – European Union, already in complete negotiation with the US

- 35% – Canada: raising the level compared to the 25% previously announced

- 30% – Mexico

- 25% – Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Kazakhstan, Tunisia, Brunei, Moldova

- 20% – Philippines

In the letters sent to the various countries, it is worth noting some points:

Of all the affected countries, only three have finalized their agreements: the United Kingdom, Vietnam, and Indonesia. A truce was signed with China. Press reports provide few details about the concessions offered and reaffirm that the parties are continuing the negotiation process. These deals are not announced through joint communiqués, as is diplomatic tradition, but simply through posts by President Trump on his social media. It should be emphasized that these agreements are not considered binding, and there are doubts, in the case of Vietnam, that the content has been fully agreed upon.

Note that, since the tariff announcements on April 2 ("Liberation Day"), not all tariffs have been effectively implemented. Financial Times columnist Robert Armstrong coined the expression "TACO": Trump Always Chickens Out. This jocular expression has become popular in Wall Street parlance and among investors, referring to Trump's pattern of announcing aggressive tariff policies and then backing down in the face of economic pressure.

There is no guarantee, however, that this will continue to happen, despite the potential adverse effects of tariffs. While the market reaction was adverse in April, at this point (July 2025), investors do not seem to believe the tariffs will have a devastating effect on the US economy. Indeed, trade flows and prices tend to adjust – even though they may cause considerable losses to the affected countries.

The feeling, in this back-and-forth of measure announcements, is that the targets are constantly being shifted, as are the deadlines, the affected sectors, and the reasons for them. Economic agents have already sued the US courts in an attempt to reverse the tariffs.

Governments and businesses must be prepared for an extended period of uncertainty and volatility, which are the hallmarks of the Trump administration. The only specific deadline is the midterm elections on November 3, 2026. Until then, many changes will undoubtedly occur.

It is also worth noting the lack of collective action or coordination among the affected countries in responding to the tariff announcements. This is because the reasons – and tariff levels – designated are different for each country. It is also due to the fear that one country will abandon the others and take individual advantage (the so-called "Prisoner's Dilemma"). Remember that all politics are local – each country sees different advantages and disadvantages in negotiating with the Trump administration. It is primarily due to the lack of leadership for such collective action. In recent history, two crises have had radically different international responses: the 2008 financial crisis (with successful coordination within the G20) and the COVID-19 epidemic (where international coordination failed miserably).

There appears to be no appetite for international coordination in the response to President Trump, beyond initiatives such as a rapprochement between the European Union and the countries of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). It is worth noting that, despite the BRICS rhetoric, China has signed a truce with the US, while Brazil is now threatened with 50% tariffs and a Section 301 investigation.

In terms of revenue, with the implementation of the 10% base tariff, according to data published by the Tax Foundation, the US could potentially collect, under various scenarios, up to a total of US$1.7 trillion over a decade (Tax Foundation 2024).

In short, in just a few months, the modus operandi of the new US administration's trade policy has become clear. The traditional and unsophisticated instrument of import tariffs has been removed from trade manuals and used as a tool to extract concessions from international partners through coercion. With back and forth, the US promises to achieve, in a few months, what the WTO has failed to achieve in decades: reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers for its trading partners. Furthermore, tariff policy is clearly being used to impact China severely. As a result, the US economy is being tested by one of its most significant challenges – that of disengaging from China, or establishing a new agreement, a new framework for bilateral relations, which will evolve positively or negatively depending on the power struggle between the defending hegemonic power and the challenger.

THE FIRST ECONOMIC IMPACTS

The advances and retreats of President Trump's actions not only created a climate of great uncertainty in the trade policies of international partners but also affected the activities of large corporations, which were forced to postpone production activities and investment decisions. As these positions intensified, the uncertainty reached the financial markets. Forecasts for the performance of the US economy and other countries began to reflect the current tension. Numerous studies by international institutions, financial institutions, and consulting firms revealed an alarming picture in the wake of these developments. Some examples are listed below.

Considering the reciprocal tariffs framework and their economic impact, JP Morgan estimated, based on 2024 data (FT, JP Morgan, see Valor Econômico 2025), that the average US tariff before the changes was 2.3%. With only the 20% increase for China, the tariff would rise to 5%. With the effect on steel and aluminum in Canada and Mexico, the tariff would rise to 7%. With the general increase for autos of 25%, including Canada and Mexico, the average tariff would rise to 10%. After April 2, the average tariff would rise to 23.3%. With the response to China's retaliation, the tariff would reach 25%. If China's exports were eliminated and all partners paid the 10% tariffs, the average tariff would fall to 12%. To get an idea of the impact on US Gross Domestic Product (GDP), JP Morgan (Valor Econômico 2025) revised US economic data from 1.3% growth to a 0.3% GDP contraction for 2025. The unemployment rate would rise to 5.3%. Inflation, measured by PCE (consumer expenditures), would rise to 4.4%, above the 2% target.

The impact was also felt in oil prices. With the economic crisis and instability in financial markets, and given inflation and recession projections, Brent prices fell from US$80 before the crisis to nearly US$60, creating uncertainty about the viability of shale oil production in the US.

WTO studies have analyzed the impacts of reciprocal tariffs. The Organization believes that global trade growth, previously estimated at 3%, would contract by 1%. The decline in global GDP would also be significant, around 1% (WTO 2025). Trade in goods between China and the US, which reached US$700 billion in 2024, could decrease by 80% or be eliminated, depending on the reactions of both parties. The study estimates that approximately US$580 billion, corresponding to bilateral exports between China and the US, would seek markets in third countries.

Furthermore, the WTO expresses concern about the effects of the fragmentation of global trade along geopolitical lines. Estimates that the division of world trade into two blocs would lead to a 7% reduction in long-term global real GDP (WTO 2025). According to the WTO, in a trade war scenario, China would have the most to lose, since in 2024, China had a US$260 billion surplus with the US, representing a 6% increase compared to 2023.

The WTO Director-General, at the ceremony celebrating the Organization's 30th anniversary, reiterated that, despite the uncertainties, of the global total of US$24 trillion in goods, 74% of international trade in goods still operated under WTO multilateral rules. This fact attests to the realityfact that, despite the conflict, the vast majority of countries still trade by WTO rules.

Financial Markets

With the announcement of the reciprocal tariff package on April 2, the US financial market reacted to the uncertainty generated. Given the release of numerous estimates of the adverse effects of tariffs on GDP and inflation, the stock market fell. However, it was the effectimpact of the tariffs on the US government bond market that had the most significant impact, leading the president to backtrack and announce a 90-day pause before imposing the tariffs, awaiting negotiations with the approximately 75 countries that had reportedly expressed interest in talks with US authorities. As noted above, the basic 10% tariff for all countries was maintained, as was the 145% tariff against China.

The reasons that led the president to backtrack on implementing his tariff package have been examined by numerous analysts. Chief among them was the reaction of the financial market. Hours before the pause was announced, given the current uncertainty, the market began demanding interest rates of 4% to 5% to roll over US debt in 10- and 30-year T-bonds, from a level of around 2%, which strongly affected the prices of these bonds. Considered a haven for investments in times of economic crisis, along with gold bullion, the market demand was considered a clear signal of the dollar's role as the central currency in the system. News reports in financial newspapers on April 9 highlighted intense criticism of the package by numerous analysts and economists, as well as evidence that several countries, including China, were shifting their reserve positions in dollars, which would have further depressed the bond prices. This episode shed light on the relationship between tariffs and finance, something not always understood by decision-makers.

Technical Issues to Be Addressed in Negotiations

Following the adoption of the tariff package and the announcement of the pause, several countries contacted US government officials to begin negotiations. The complexity of the exercise was then highlighted. The objective of the US package would be to lower the levels of tariff and non-tariff barriers of its partners. On the one hand, tariff values are objective data, but this does not apply to numerous other regulatory barriers imposed on US exports to other countries. These include: value-added taxes (VAT), import licenses, technical, sanitary, and phytosanitary measures, environmental measures that affect trade, divergent criteria from the US in imposing standards (e.g., how to measure the carbon content of manufactured goods), and environmental regulations. Added to this list are issues related to the defense of intellectual property, in addition to the bureaucracy of customs procedures. The question would be how to convert regulatory barriers into tariff equivalents.

In a market access negotiation process, estimates of tariff equivalents are made for each type of regulation and each type of product. These calculations are complex and require prior methodology definition. The difficulty of how such a task could be accomplished in a short period of time was raised.

A relevant point of discussion is the USTR's annual publication of updated versions of the US Trade Policy Barriers report, which allows US partners to have advanced knowledge of the barriers raised by US experts regarding each country. Another relevant source is the discussions of the WTO's Trade Policy Review, in which the US always plays an active role in discussions of the trade practices of WTO members.

The central question is how all US concerns can be resolved in bilateral negotiations, country by country, and simultaneously. Plurilateral negotiations often last years, as is the case with preferential agreements.

THE MAIN CRITICISMS OF THE TARIFF PACKAGE

The America First Trade Policy memorandum, released on the first day of President Trump's second term, made clear the president's predilection for using tariffs as weapons of coercion.

In the first days of the package's implementation, reactions from various sectors of the economy began to be heard. Eminent economics professors, former secretaries of Democratic administrations, and economic analysts were emphatic in their criticism of the Trump Package. They pointed to the inflationary impacts and the potential recessionary scenario for the US economy and its global effects. Some points deserve attention:

FROM GEOECONOMICS TO GEOPOLITICS: POSSIBLE SCENARIOS

Given the uncertainties generated in these first months of the Trump administration, and the broad repercussions of the measures on the global economy and value chains, there is considerable interest among economic agents and decision-makers in possible future scenarios.

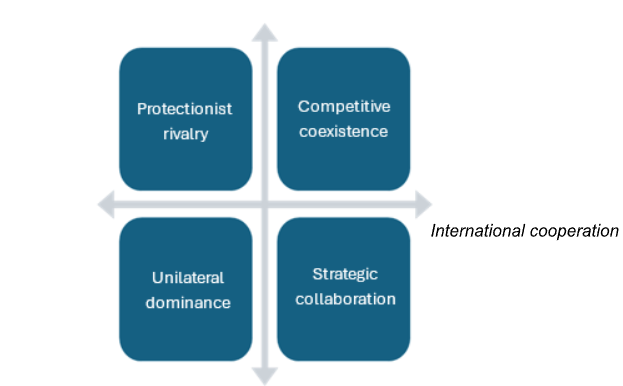

Scenario construction necessarily involves theoretical assumptions that guide the likelihood of potential events and behaviors. When it comes to international trade, two axes can help structure the scenario construction plan: the level of global tensions (shown on a vertical axis) and the dynamics of international cooperation (horizontal axis). The intersection of these two axes results in four scenarios: protectionist rivalry, strategic collaboration, competitive coexistence, and unilateral dominance (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scenarios based on do Prado et al. (2025).

Note that these scenarios are not mutually exclusive and may overlap in various ways. They are clearly theoretical, hypothetical, and may seem exaggerated in their description of futures. Scenarios are not predictions, but rather a schematic way of imagining possible futures. The actual trajectory of international trade will likely involve elements of each of these four scenarios. The actual trajectory will be shaped by complex geopolitical and geoeconomic dynamics, such as those we are currently experiencing with the tariffs adopted by the US government, the instability resulting from unilateral actions, the responses and behavior of other trading partners, and also by random factors, such as those experienced with the pandemic, natural disasters, or conflicts.

Scenario 1: Protectionist rivalry

High global tension and low international cooperation

This is the worst-case scenario, characterized by rising tariffs and trade barriers, retaliation, nationalist industrial policies geared toward self-sufficiency, and limited cross-border investment. Protectionist rivalry spreads beyond the US and China. Rising tensions and widespread disregard for international agreements create an environment for potential armed conflict.

Driven by the political need to respond to US tariffs and concerns about unfair competition and national security, several countries attempt to minimize the effects of each other's barriers by raising their barriers and protecting their investors and markets. The US exponentially escalates trade tensions, eroding the multilateral trading system, and generating retaliatory responses, resulting in increased protectionism worldwide.

China responds with increasing retaliatory measures, trade and investment barriers, and restrictions on the export of critical raw materials, and massive interventions in the US debt market. This further increases trade and economic tensions, leads to a deeper fragmentation of the global trading system, and generates a global recession. Global supply chains suffer significant disruptions.

The US insists on controlling the Panama Canal and occupying Greenland. A Chinese-caused crisis in the Taiwan Strait generates growing geopolitical tensions. Critical raw materials, many of which are mined and refined by China, become commercial weapons as trade restrictions and supply bottlenecks limit access to essential inputs for the production of high-tech goods in the US. International trade is disrupted, and the global economy enters a recession.

Scenario 2: Strategic collaboration

Low global tensions and high international cooperation

In contrast to Scenario 1, this is a hypothesis of positive developments, in which governments prioritize global trade agreements and standards and engage in structured dialogues to address shared challenges of efficient production and attempt to resolve imbalances rationally. A shared order is built to ensure the smooth flow of trade, and geopolitical tensions are low.

In this scenario, international cooperation is high, with joint efforts to build and maintain resilient and secure supply chains. China and the US establish a framework of permanent consultations and negotiations to reduce tensions and resolve trade issues. The US, China, and other trading partners promote joint ventures between their companies and common projects, encourage investment with agreed technology transfer and job creation, secure the supply of critical minerals, and share innovation.

Value chains are maintained and strengthened, generating increasing production efficiency. Other countries benefit from the climate of détente and cooperation.

Scenario 3: Competitive coexistence

High global tensions and high international cooperation

Unlike the two previous scenarios – which are either negative or positive – this scenario paints a mixed picture, in which competition and cooperation coexist. While some countries may engage in protectionist measures, others prioritize collaborative efforts.

Many governments recognize the need to maintain value chains while addressing concerns about fair competition and national security. Many countries implement trade defense measures and safeguards on Chinese products or "gray area" measures (voluntary export restrictions) with the US and China, while also engaging in strategic partnerships and dialogues. This is a balancing act, encompassing a series of actions, following a well-developed strategy.

This scenario results in a high degree of regionalization, with countries forming trading blocs and prioritizing domestic economic goals while continuing to participate in global trade.

Scenario 4: Unilateral dominance

Low global tensions and low international cooperation

In this scenario, one region or country dominates the production of goods due to its technological leadership, domestic market size, and control over critical resources. China, with its dominance in high-tech and software production, leverages its competitive advantages to capture a large share of the global market and assume leadership in the global economy.

Advances in Chinese technology and its vast domestic market boost the production of Chinese companies, which spread throughout the world. The US dollar ceases to be the primary payment and international reserve currency. With the decline and recession of the US, China has become the center of the global economy.

The international trade order is coming to be dominated by China and its companies. Chinese high-tech products gain ground in global markets. US companies face a structural crisis, with the US recession and the instability generated by their governments' misguided decisions.

Other regions become dependent on Chinese technology and supply chains. This results in a less diversified industry and production structures, with limited competition to reduce costs and accelerate technological advancement in other regions.

Possible scenario

The recent actions of the US government described in the first part of this policy paper have generated a high degree of instability and uncertainty in international trade. In addition to the repercussions on current business, this instability – a hallmark of Donald Trump – will tend to dampen the climate for direct productive investment. It is unlikely that companies will decide, in a few months, to transfer their manufacturing operations en masse to the US. Most likely, most economic agents will decide to wait for greater definition (if not stabilization) of the tariff and business framework in the US.

The disregard for bilateral and regional preferential agreements, tariff concessions to developing countries, and the violation of fundamental WTO rules (tariff consolidation, the Most Favored Nation clause, and national treatment), in addition to the back-and-forth in the discretionary application of tariffs, have generated distrust and discredit among economic agents toward the United States. Decision-makers in the United States' main trading partners (China, the European Union, and Japan) are now adopting a strategy of minimizing exposure to the risk posed by the Trump administration (derisking).

The loss of confidence and credibility in the United States has already become evident in the behavior of the capital markets and American debt securities. Despite its vibrant consumer market, the United States has become an unreliable partner. This is mainly due to the erratic behavior of its leader and his advisors, and the lack of consistency in the measures adopted thus far. Although likely in an attempt at ex-post rationalization, some commentators may see a method and strategy for reordering the American and global economies behind these measures, based on the texts and explanations of Stephen Miran, Scott Bessent, and Howard Lutnick. Most observers, however, see weak and questionable theoretical and empirical foundations in the published texts and explanations given thus far.

The system of checks and balances governing the separation of powers between the Executive, Legislative, and Judiciary branches has practically ceased to function in the United States. Trump is now the president with unprecedented powers in US history, as demonstrated by the explosion in the number and content of executive orders issued since January 2025. The only counterweight that has worked so far has been the power of the markets, especially the bond market, which signaled a risk of financial crisis the day before the 90-day pause in tariffs. Other potential (but far from guaranteed) counterweights will be consumer/voter behavior, should there be a significant increase in inflation and a reduction in economic activity, and possibly campaign donations to Republican candidates in the midterm elections, starting at the end of 2025. It will also be interesting to monitor the opinions and behavior of the Wall Street investment community and the so-called Tech-bros, bosses of large technology companies, who have significant influence over Donald Trump.

Observing the first 100 days of Trump's second presidency, several trends can be identified, which should be confirmed (or not) in the coming months. The first is that China has behaved firmly and calmly, demonstrating its preparedness for the current turmoil. To the erratic behavior of Donald Trump's The Art of the Deal, China responds with the age-old patience of Sun Tzu's The Art of War. Informally, one could say that the score of the first 100 days is China 1-0 USA. The extent to which China influenced the Treasury bond market's behavior is still debated, but there are indications that such influence was not negligible.

The second trend – related to the first – is that, from now on, the relationship between the capital and debt markets – that is, between the world of finance and trade policy measures (tariffs) – is fully intertwined. This direct relationship between the two worlds – finance and trade – raises interesting questions, mainly because the international governance systems of each differ in their level of regulation, locus, and epistemic communities. This relationship has already been clear in the past, especially during the 2008 financial crisis. However, now it takes on even more precise contours, given the mutual influence and power struggles at the top of the US government.

The third trend is the declining centrality of the United States in the global economy. The rise in "US risk," with the uncertainty and instability generated by the Trump administration, coupled with the economic rise and technological development of China, which is unafraid to confront President Trump's tariff action, points to a growing role for that country on the international stage and a diminishing one for the United States. The US's attack on the Bretton Woods order – which they conceived and implemented, and which led them to become the wealthiest country in the world – is reminiscent of Barbara Tuchman's book "March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam" (1984), in which the author describes some of history's great paradoxes, when governments adopt policies and measures contrary to their interests. The dominance of the US dollar as a reserve currency and for international payments, previously virtually unchallenged, is now being questioned, especially in China, Southeast Asia, and the Persian Gulf countries, and is also part of the BRICS discussions. Budget cuts to major American universities and research institutions and the expulsion of international students reinforce this impression of paradox and self-destructive behavior.

How will other countries react to this new world, to what seems to be no longer an era of change, but a change of eras?

For now, the other major economies – the European Union, Japan, India, the United Kingdom, and Brazil – have adopted a moderate, restrained attitude toward the instability provoked by the US. This attitude, of course, could change if the US reintroduces prohibitive tariffs or eventually forces these countries to choose between an alliance with the US or China. An attempt to form agreements between blocs, such as the European Union and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), is beginning to emerge – albeit tenuously. The big question will be whether the US will be able to negotiate comprehensive and constructive agreements (and above all, whether they will be respected), based on a coercive attitude, with the threat of imposing tariffs, and to form a new international order, no longer based on multilaterally agreed rules and preferential agreements, but simply on the desire (or need) to continue exporting to the American market.

World Trade Organization

The tariff measures adopted by Donald Trump since January 2025 constitute a frontal attack on the fundamental rules of the WTO. US doubts and questions regarding the WTO, however, are not exactly new. Since 2008, when Director-General Pascal Lamy attempted to propose a framework agreement to conclude the Doha Round, the US's difficulties with the Organization were evident. Following China's successful challenge to the Appellate Body of trade defense measures adopted by the US in the 2000s and 2010s, US representatives have become harshly critical of the WTO's actions, accusing it – not without reason – of legal activism and interpretations inconsistent with the Uruguay Round negotiations. The US has also begun to strongly criticize China's state capitalism model and subsidies at the WTO, which cause profound distortions in international trade. The US considers the Chinese production model to be incompatible with the fundamental principles of a market economy defended by the WTO. The US has begun blocking the appointments of members of the Appellate Body, which ceased operations in 2019. It should also be noted that all proposals to attempt to continue negotiations in a plurilateral format and on relevant issues, such as e-commerce, have been obstructed by India and South Africa, further weakening the WTO's negotiating role.

The recent announcement by the US that it would no longer contribute to the WTO budget and the news that a bill has been introduced in the House of Representatives to withdraw from the WTO raise questions about the future of the US within the WTO and of the WTO itself.

What alternatives are available as a result of this US stance? The first would be the abandonment of the Organization by other members, given the US's disengagement. This scenario seems unlikely, particularly given the continued support of the European Union, Japan, Australia, Brazil, and others for the WTO and its role as a transparency platform for international trade dialogue. According to a January 2025 WTO Secretariat calculation, approximately 80% of global merchandise trade is conducted under the Most Favored Nation Clause (Gonciarz & Verbeet 2025). Even if the tariffs adopted by the US negatively impact this percentage – particularly in bilateral trade between China and the US, which, according to the WTO, should virtually constitute a "decoupling" of the two economies (Stewart 2025) – trade between other countries should continue to be conducted primarily under multilateral tariffs. It should also be noted that the more than 300 existing preferential agreements are based on the tariffs and commitments undertaken by their WTO participants, from which preferential tariffs and rules are established – that is, the basis of all regional and preferential agreements continues to be the WTO agreements.

The second alternative would be a WTO minus one configuration, either through the formal withdrawal of the US or through its complete disengagement. This alternative seems realistic, as it is unlikely that the US will lead a reform of the WTO from within. More likely, its role would be reduced to a minimum – or it would actually request its formal withdrawal. In this configuration, the question will be what role China would assume in the Organization and whether it would be capable of leading consensus on agreements such as the Investment Facilitation Agreement and other topics. It would also be interesting to envision a renewed dispute settlement mechanism.

A key point is the role that China, the European Union, and other middle powers such as Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom, India, Brazil, and Indonesia will play in the WTO and the future configuration of world trade. Coordination between these countries and the world's smaller economies could give new impetus to the Organization.

CONCLUSION

The tariff measures adopted by the US government since President Donald Trump's inauguration in January 2025 represent a rupture in the rules-based multilateral trading system in place since the creation of the GATT in 1947 and the establishment of the WTO in 1995. The US, whose hegemony is now challenged by China, has given up paying the price for leadership in a system that enabled it to be the wealthiest and most militarily powerful country on the planet. The Pax Americana, which prevailed since the end of World War II, presupposed a political will on the part of the US to exercise external leadership. That will no longer exist. Currently, the primacy of domestic politics, based on the slogan "Make America Great Again" (the "again" presupposes and acknowledges that today's America is no longer "great"), is evident.

This lack of political will to exercise global leadership is due to the rise of China as a challenging hegemonic power. China's dazzling economic rise, contrary to what many believed in 2001, did not lead to a change in the country's political regime. On the contrary, it strengthened and consolidated the Chinese Communist Party. The US has never had a rival like China, whose economy now accounts for nearly 70% of US GDP and boasts enviable technological development. China has come to exercise not only economic and technological leadership, but also political leadership in Asia, with a strategic alliance with Russia. China is now the largest trading partner of virtually all of Africa, Latin America, and Asia, with few exceptions.

This opens a new strategic cycle in which the US appears to be abandoning the rules-based multilateral liberal order and creating instability, at the cost of its credibility as a reliable partner. The Trump administration's actions will, from now on, imply that the US will accept a division of the world into large regional economic spaces and a new configuration of polarities. The Trump administration has precipitated this epochal shift, in which the absolute centrality of the United States in the global economy is being challenged, opening the way for other powers to challenge that position. None of this, however, is guaranteed. One hypothesis is that markets will adapt to the new conditions and that the United States, with its immense consumer market, by far the largest on the planet, will continue to exert its power to attract investment and also remain a central hub of technological innovation.

New analyses and discussions are on the agenda: will the world of the near future be led by three, two, or one hegemonic power? In the gradations of global tensions and international cooperation, which scenario will prevail?

References

Band Jornalismo. 2025. União Europeia suspende tarifas contra Estados Unidos e busca negociação | BandNews TV. YouTube video, 19:27. Publicado em 10 de abril de 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLOK--vFkdo.

Blackwill, Robert D., and Jennifer M. Harris. 2016. War by Other Means. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

do Prado, Vera, Elvire Fabry, Arancha González Laya, Nadine Köhler-Suzuki, Pascal Lamy e Svenja Praetorius. 2025. “The Road to a New European Automotive Strategy: Trade and Industrial Policy Options.” Report no. 129. https://institutdelors.eu/en/publications/the-road-to-a-new-european-automotive-strategy-trade-and-industrial-policy-options/.

Estados Unidos. 2025a. American First Act. Washington, DC: The White House. 20 de janeiro.

Estados Unidos. 2025b. Reciprocal Trade and Tariff. Washington, DC: The White House. 2 de abril.

Estados Unidos. 2025c. Fair and Reciprocal Plan. The White House, 2 de abril de 2025.

Gonciarz, Tomasz & Tessa Verbeet. 2025. Significance of Most Favoured Nation Terms in Global Trade. WTO Staff Working Paper, 15 de janeiro de 2025. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd202502_e.pdf.

Miran, Stephen. 2024. A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. Hudson Bay Capital, novembro de 2024. https://www.hudsonbaycapital.com/documents/FG/hudsonbay/research/638199_A_Users_Guide_to_Restructuring_the_Global_Trading_System.pdf.

OMC. 2025.Outlook for World Trade in 2025. WTO, Abril de 2025. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/trade_outlook25_e.htm.

Stewart, Heather. 2025. “Trump Tariffs Will Send Global Trade into Reverse this Year, Warns WTO”. The Guardian, 16 de abril de 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/16/trump-tariffs-will-send-global-trade-into-reverse-this-year-warns-wto.

Tax Foundation. 2024. Trump Tariff: The Economic Impact of Trump's Trade War. 10 de abril de 2024. https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/trump-tariffs-trade-war/.

Tuchman, Barbara. 1984. “March of Folly: from Troy to Vietnam.” The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam. Reino Unido: Crux Publishing Ltd, 2015.

Valor Econômico. 2025. J.P. Morgan Chase tem lucro líquido de US$ 14,6 bilhões no 1º trimestre. Valor Econômico, 11 de abril de 2025. https://valor.globo.com/financas/noticia/2025/04/11/jp-morgan-chase-tem-lucro-liquido-de-us-146-bilhoes-no-1o-trimestre.ghtml.

Received: April 21 2025

Accpeted for publishing: April 27 2025

Updated: July 18 2025

* Translated by Catarina Werlang with the support of digital machine translation tools: Google Translate (initial draft), Grammarly (grammatical and syntactic revision), and ChatGPT (selective phrasing refinements).

Copyright © 2025 CEBRI-Journal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.